[This post is part of an ongoing challenge to understand 52 papers in 52 weeks. You can read previous entries, here, or subscribe to be notified of new posts by email]

The Myriad Virtues of Wavelet Trees is a 2009 CS paper written by Ferragina, Giancarlo, and Manzini. The holiday cheer the past few days made this one hard to understand and write about ... something about focus.

It talks about using Wavelet Trees as a stand-alone compression algorithm and as on top of some popular string encodings like run-length encoding, move-to-front transform and the Burrows-Wheeler transform. The results are pretty cool, but not revolutionary. The authors just improved some additive terms in lower and upper bounds of achievable compression.

Background knowledge

Before we can get into the meat of this paper, you'll need to know about Wavelet Trees and run-length encoding and Burrows-Wheeler and stuff. On my first run-through I didn't pay attention in this section and spent the rest of the paper very confused.

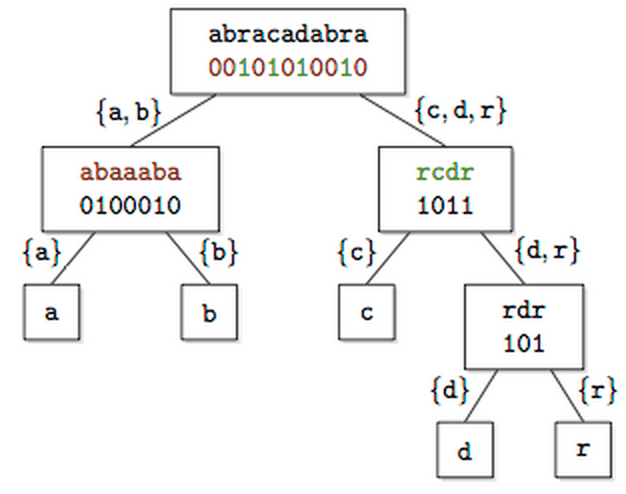

Wavelet Trees recursively partition the source alphabet into pairs of subsets, then mark which branch of the tree a particular symbol goes into. To reconstruct elements at you just walk the tree until you find the leaf and voila, done.

Phew, that was simple. Now we just need the transforms.

We can do to lower the entropy of a string to make it easier to compress. Entropy is a measure of how disorganised our string is. You can also think of it as information density.

The paper references two transforms whose aim is to turn a fuzzy string into a string with many runs of the same character: move to front and Burrows-Wheeler transform.

Move to front transform encodes strings into numbers with the help of an indexed alphabet. Every time you replace a character with its index, you move it to the front and re-index. Given a 25-letter English alphabet indexed from 0 to 25 the string bananaaa becomes 1,1,13,1,1,1,0,0.

To reverse the encoding you just re-do the same algorithm again, except replacing indexes with characters.

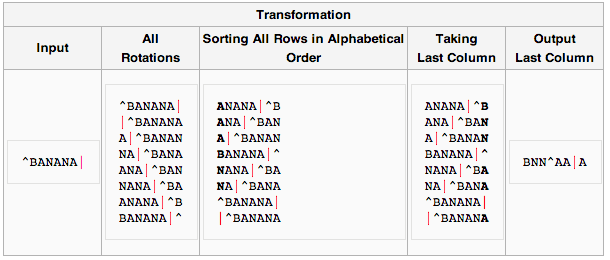

The Burrows-Wheeler transform is a bit more complicated. This one uses sorted rotations of a string. Basically, take all permutations, sort them alphabetically, take the last column.

Reversing a transformed string is simple as well - take the transformed string and sort it. Now you have two columns. Take these pairs of characters and sort them to create more columns. Repeat until you have all the permutations of the original string and take the one where the end-of-file character is last. Voila.

After you have a string transformed into a form with less entropy there are a number of things you can do to compress it. For instance, run-length encoding where runs of successive characters are replaced with a count of repetitions and the character. It's not used much on its own anymore, but made a killing compressing simple black&white images back in the day.

What we're looking to achieve

So how can wavelet trees help make all this better?

The authors analyse Wavelet Trees as stand-alone compressors and as compressors of run-length encoded strings - RLE Wavelet Trees - and gap encoded string - GE Wavelet Trees. They also show a theoretical justification for Wavelet Trees being better in practice than move-to-front coding.

The meat of the article is using Wavelet Trees to compress the output of the Burrows-Wheeler transform and introducing the concept of Generalised Wavelet Trees, which can reach compression almost on the level of theoretical bound for optimal coding even for mixed strings.

Ultimately, we're going to beat the theoretical compression limit H0 = -Σi=1h(ni/|s|) log (ni/|s|) for fixed codewords. Otherwise known as 0-th order entropy. This is the most we can compress a string by always replacing the same symbol with the same codeword.

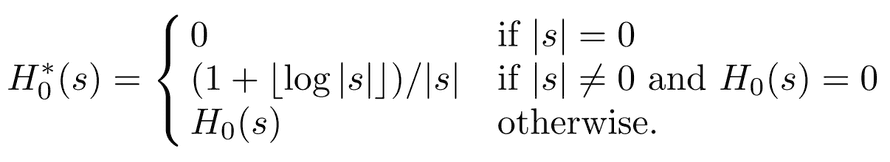

For highly compressible strings this bound doesn't make much sense, so the authors found a better one, H0*:

Our approach is going to beat this by having symbol codewords depend on k preceding symbols, giving us k-th order entropy of Hk(s)* - the maximum achievable compression by looking at no more than k preceding symbols.

Achieving 0-th order entropy

Let CPF denote a prefix-free encoding with a logarithmic cost of a log n + b for n ≥ 1. Codes where a is higher than 2 wouldn't be very efficient for reasons the paper assumes we understand, so we're only looking at those where a ≤ 2. This means that b ≥ 1; for the rest of our discussion we can assume that a ≤ 2b and a ≤ b+1.

To combine wavelet trees and run length encoding for a string we first define a compressor CRLE(s) = a1CPF(l1)CPF(l2).... Which is a fancy way of saying we prefix-encode runs of symbols, but store the first symbol in full.

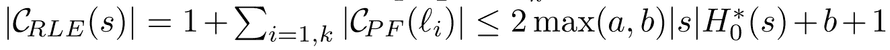

This has a lower bound with a glorious equation, essentially saying that the length of a CRLE(s) string is the sum of its parts and is shorter than twice the length of s multiplied by H0(s)* and b+1.

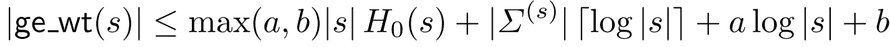

Now we can combine wavelet trees and run length encoding into 'rlewt', or RLE Wavelet Trees, which first encodes the string with _CPF to make a Wavelet Tree, then compresses its internal nodes with CRLE. This produces shorter strings than just CRLE with a bound of:

I'm not entirely certain I understand why this equation says the bound is lower than before, so let's just believe the authors. This produces better compressed strings.

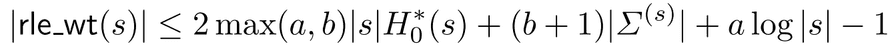

For string 'dabbdabc' our algorithm would produce a skewed Wavelet Tree, with 'b' in the left-most leaf since it appears the most.

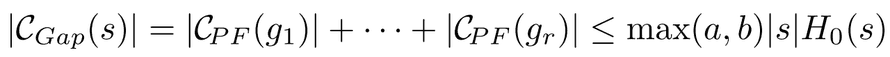

To get GE Wavelet Trees, 'gewt', we first define a gap encoding called _CGap, which encodes binary strings by noting where 1's are located in the string. This creates a lower bound for compression of:

As with CRLE before, we make a Wavelet Tree from our string then use CGap to encode the internal nodes. Because we're just encoding the number of occurrences of a substring between boundaries, we can compress strings very well.

RLE wavelet trees and bwt

It turns out that using RLE Wavelet Trees as a post-processor for the Burrows-Wheeler transform, we can achieve that mythical Hk* compression. But it doesn't work at all with GE Wavelet Trees.

The key is to remember that 'bwt' is a tool for achieving Hk* as long as we can achieve H0* for every partition. But apparently if we slice the Wavelet Tree according to 'bwt' partitions we get something called a full Wavelet Tree, which doesn't actually improve compression.

Instead we have to use pruned Wavelet Trees, which the authors don't really explain. They give a proof that adding Wavelet Trees on top of 'bwt' is beneficial, which I won't try to reproduce here since a large part of it is skipped and put in "the full version".

Their final conclusion is that Wavelet Trees act as a sort of compression booster for the Burrows-Wheeler transform, but impose a run-time cost that is non-negligible.

Finally, they conclude that GE Wavelet Trees don't work together with 'bwt' because global choices need to be made about things like tree shape and the role of 1's and 0's in nodes. Bummer.

Generalised wavelet trees

Three things affect a Wavelet Tree's cost: its binary shape, the assignment of alphabet symbols to leaves, and the possibility of using non-binary compressors for nodes. To address these issues, the authors introduce so called Generalised Wavelet Trees.

Let's use two compressors - C01 is specialised for binary strings (RLE for instance), and CΣ is generic (Huffman coding for instance). We're going to assume they satisfy three properties:

a) |C01(x)| ≤ α|x|H0(x) + β* bits for a binary x, where α and β are constants. b) |CΣ(y)| ≤ |y|H0(y) + η|y| + µ bits for a generic y, where η and µ are constants. c) the running time of C01 and CΣ is a convex function and their working space is non-decreasing

Basically we've defined the limit of the longest strings produced by our compressors and decided that we should be able to use them in practice.

Now we define a leaf cover, L, as a subset of nodes in a tree Wp(s), if every leaf has a unique ancestor in L. Then WpL(s) is the tree with all nodes in L removed. We colour WpL with red and black so that leaves are black and all remaining nodes are red.

Then we use the binary compressor for all binary strings in WpL and red stuff, and the generic compressor for non-binary strings and black. As usual we ignore the leaves. Our new cost is the number of bits produced - |C01(s01(u))| from red nodes and |CΣ(s(u))| for black nodes.

According to the authors, coming up with a way to decode this encoding is trivial, and the whole thing is somehow "better". I don't quite get why it's better, but I'm probably missing something.

There are, however, two optimisation problems with this approach: finding the minimal leaf cover that minimizes the cost function C(WpL(s))*, and finding the optimal combination of Wavelet Tree shape and and assignment of binary and generic compressors to nodes to produce the shortest string possible.

They've provided a sketch of the algorithm to solve these, but ultimately a sketch does not a solution make.

Fin

So there you have it, Wavelet Trees used for compressing strings after applying the Burrows-Wheeler transform to make it easier. I'm not sure whether this is used anywhere in the real world, but it looks interesting.

Continue reading about Week 10, The myriad virtues of Wavelet Trees

Semantically similar articles hand-picked by GPT-4

- Science Wednesday: Towards a computational model of poetry generation

- Week 2: Level 1 of Super Mario Bros. is easy with lexicographic orderings and

- Week 1: Turing's On computable numbers

- Eight things to know about LLMs

- Minimum substring cover problem

Learned something new?

Read more Software Engineering Lessons from Production

I write articles with real insight into the career and skills of a modern software engineer. "Raw and honest from the heart!" as one reader described them. Fueled by lessons learned over 20 years of building production code for side-projects, small businesses, and hyper growth startups. Both successful and not.

Subscribe below 👇

Software Engineering Lessons from Production

Join Swizec's Newsletter and get insightful emails 💌 on mindsets, tactics, and technical skills for your career. Real lessons from building production software. No bullshit.

"Man, love your simple writing! Yours is the only newsletter I open and only blog that I give a fuck to read & scroll till the end. And wow always take away lessons with me. Inspiring! And very relatable. 👌"

Have a burning question that you think I can answer? Hit me up on twitter and I'll do my best.

Who am I and who do I help? I'm Swizec Teller and I turn coders into engineers with "Raw and honest from the heart!" writing. No bullshit. Real insights into the career and skills of a modern software engineer.

Want to become a true senior engineer? Take ownership, have autonomy, and be a force multiplier on your team. The Senior Engineer Mindset ebook can help 👉 swizec.com/senior-mindset. These are the shifts in mindset that unlocked my career.

Curious about Serverless and the modern backend? Check out Serverless Handbook, for frontend engineers 👉 ServerlessHandbook.dev

Want to Stop copy pasting D3 examples and create data visualizations of your own? Learn how to build scalable dataviz React components your whole team can understand with React for Data Visualization

Want to get my best emails on JavaScript, React, Serverless, Fullstack Web, or Indie Hacking? Check out swizec.com/collections

Did someone amazing share this letter with you? Wonderful! You can sign up for my weekly letters for software engineers on their path to greatness, here: swizec.com/blog

Want to brush up on your modern JavaScript syntax? Check out my interactive cheatsheet: es6cheatsheet.com

By the way, just in case no one has told you it yet today: I love and appreciate you for who you are ❤️