At this week's livecoding session, I mentioned mutating ASTs to improve the performance of our faux AI that writes JavaScript algorithm. It would help us converge on a solution faster.

But what is an AST?

Well, it's an abstract syntax tree. It's that thing computers use to understand your code. Let me explain how they work. I think every programmer can benefit from knowing this stuff.

It took my compilers professor in college a few hours. Let's see if I can show you the gist of it in a few hundred words. With a picture or two.

We're going to use Babylon to parse code into an AST and Prettier to print it back out into code. Coincidentally, that's how Prettier approaches making your code pretty. You'll see that too.

We begin with a test harness runnable in node.js.

const util = require("util");

const babylon = require("babylon");

const code = `

`;

let AST = babylon.parse(code);

console.log(util.inspect(AST, false, null));

We're going to put the code we're testing into code. The rest is there to parse it and print the resulting AST. babylon.parse is where the magic happens.

Parsing an empty piece of code creates an AST like this:

Node {

type: 'File',

start: 0,

end: 1,

loc:

SourceLocation {

start: Position { line: 1, column: 0 },

end: Position { line: 2, column: 0 } },

program:

Node {

type: 'Program',

start: 0,

end: 1,

loc:

SourceLocation {

start: Position { line: 1, column: 0 },

end: Position { line: 2, column: 0 } },

sourceType: 'script',

body: [],

directives: [] },

comments: [],

tokens:

[ Token {

type:

TokenType {

label: 'eof',

keyword: undefined,

beforeExpr: false,

startsExpr: false,

rightAssociative: false,

isLoop: false,

isAssign: false,

prefix: false,

postfix: false,

binop: null,

updateContext: null },

value: undefined,

start: 1,

end: 1,

loc:

SourceLocation {

start: Position { line: 2, column: 0 },

end: Position { line: 2, column: 0 } } } ] }

That doesn't tell you much, does it? It doesn't tell me anything. Most of it is for Babylon to know what's going on.

Here's the part we care about:

program:

Node {

type: 'Program',

start: 0,

end: 1,

loc:

SourceLocation {

start: Position { line: 1, column: 0 },

end: Position { line: 2, column: 0 } },

sourceType: 'script',

body: [],

directives: [] },

You can read this as "There is a program that starts at 0:1 and ends at 0:2 and has an empty body. It is a script.". That means our code isn't as empty as we thought; it's got a whole empty line!

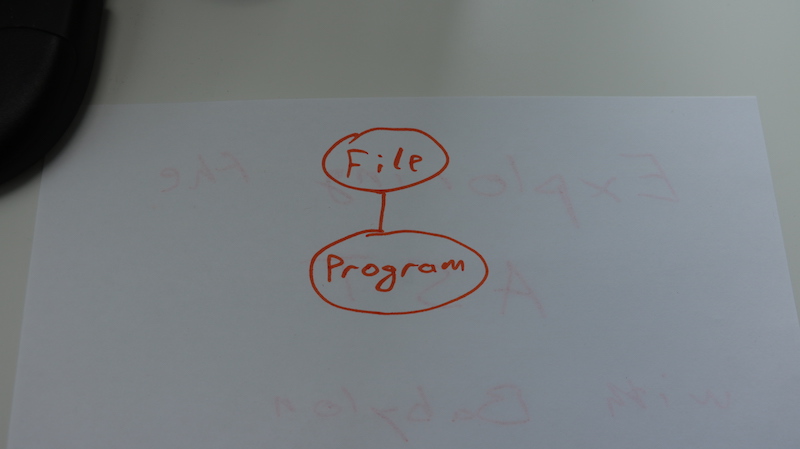

In a picture, that AST looks something like this:

Root file node, child program node.

Now let's try a variable assignment.

const code = `

let a = 5;

`;

That outputs a bigger AST. I'm going to snip out some of the details to make this readable.

program:

Node {

type: 'Program',

start: 0,

end: 12,

loc:

SourceLocation {},

sourceType: 'script',

body:

[ Node {

type: 'VariableDeclaration',

start: 1,

end: 11,

loc:

SourceLocation {},

declarations:

[ Node {

type: 'VariableDeclarator',

start: 5,

end: 10,

loc:

SourceLocation {},

id:

Node {

type: 'Identifier',

start: 5,

end: 6,

loc:

SourceLocation {},

name: 'a' },

init:

Node {

type: 'NumericLiteral',

start: 9,

end: 10,

loc:

SourceLocation {},

extra: { rawValue: 5, raw: '5' },

value: 5 } } ],

kind: 'let' } ],

directives: [] },

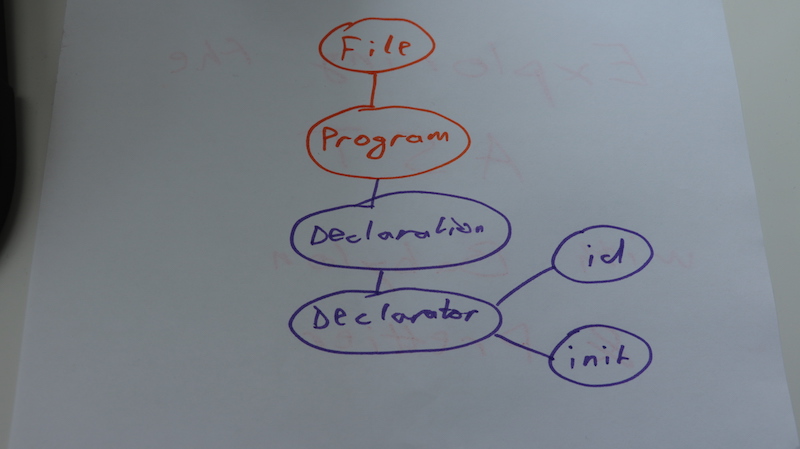

Our body now has a variableDeclaration node, which contains a variableDeclarator with an Identifier and a NumericLiteral. From this AST, you can infer that a variableDeclarator can contain multiple declarators, and that each declarator has an id and an init. The id node identifies the resulting variable and init sets its value.

In a picture, that looks something like this:

You'll notice the AST doesn't talk much about what our code says. There's no lets and equal signs or any of that. Sure, the identifier has a name and the init has a value, but the rest is an abstraction level higher.

An AST talks about what the code does, not what it is.

There's a list of tokens if you want to know what the code says:

tokens:

[ Token {

type:

KeywordTokenType {

label: 'let',

keyword: 'let',

beforeExpr: false,

startsExpr: false,

rightAssociative: false,

isLoop: false,

isAssign: false,

prefix: false,

postfix: false,

binop: null,

updateContext: null },

value: 'let',

start: 1,

end: 4,

loc:

SourceLocation {},

Token {

type:

TokenType {

label: 'name',

keyword: undefined,

beforeExpr: false,

startsExpr: true,

rightAssociative: false,

isLoop: false,

isAssign: false,

prefix: false,

postfix: false,

binop: null,

updateContext: [Function] },

value: 'a',

start: 5,

end: 6,

loc:

SourceLocation {},

Token {

type:

TokenType {

label: '=',

keyword: undefined,

beforeExpr: true,

startsExpr: false,

rightAssociative: false,

isLoop: false,

isAssign: true,

prefix: false,

postfix: false,

binop: null,

updateContext: null },

value: '=',

start: 7,

end: 8,

loc:

SourceLocation { },

Token {

type:

TokenType {

label: 'num',

keyword: undefined,

beforeExpr: false,

startsExpr: true,

rightAssociative: false,

isLoop: false,

isAssign: false,

prefix: false,

postfix: false,

binop: null,

updateContext: null },

value: 5,

start: 9,

end: 10,

loc:

SourceLocation {},

Token {

type:

TokenType {

label: ';',

keyword: undefined,

beforeExpr: true,

startsExpr: false,

rightAssociative: false,

isLoop: false,

isAssign: false,

prefix: false,

postfix: false,

binop: null,

updateContext: null },

value: undefined,

start: 10,

end: 11,

loc:

SourceLocation {},

Token {

type:

TokenType {

label: 'eof',

keyword: undefined,

beforeExpr: false,

startsExpr: false,

rightAssociative: false,

isLoop: false,

isAssign: false,

prefix: false,

postfix: false,

binop: null,

updateContext: null },

value: undefined,

start: 12,

end: 12,

loc:

SourceLocation { } ]

The list of tokens is a lot more interesting to Babylon than it is to you or I. It explains how to translate your code into a syntax tree.

For example, let's say our parser encounters the a token. Just like you, it recognizes that this is not a JavaScript reserved word. That must mean it's a name for something and it starts a new expression.

Token {

type:

TokenType {

label: 'name',

keyword: undefined,

beforeExpr: false,

startsExpr: true,

rightAssociative: false,

isLoop: false,

isAssign: false,

prefix: false,

postfix: false,

binop: null,

updateContext: [Function] },

value: 'a',

start: 5,

end: 6

}

The parser keeps going. It doesn't know yet what this new expression is going to be, but its name is a.

So it finds the = sign.

type:

TokenType {

label: '=',

keyword: undefined,

beforeExpr: true,

startsExpr: false,

rightAssociative: false,

isLoop: false,

isAssign: true,

prefix: false,

postfix: false,

binop: null,

updateContext: null },

value: '=',

Ah, so we're doing assignment, isAssign, and we're expecting an expression afterwards. At least that's what I think beforeExpr means. It's hard to know for sure because ; also gets the beforeExpr flag 🤔

Either way, Babylon then encounters a num token, which also starts a new expression. In this case, an expression that's the length of a single token, but still a new expression.

As the parser goes through these tokens, it builds a syntax tree. Some tokens build new branches; others add more children to existing nodes.

Making this work is tricky. I remember building a compiler at school, and it nearly broke my brain. The hard part is that you're reading a flat stream of tokens and converting it into a rich tree.

And yet, you do it every day when reading other people's code! Quite impressive.

Now, once you have an AST, you can use something like Prettier to print it back out into readable code.

const code = `

let

a

=

5;

`;

console.log(prettier.format(code));

// let a = 5;

I couldn't find the internal Prettier function that takes an AST and outputs it, but that's what .format does internally. Parses your code, prints it back out with less cruft.

When I have some time, I'll figure out how to manipulate those ASTs to create different code.

Now excuse me while I install Prettier in my editor. 🤓

Continue reading about Exploring the AST with Babylon and Prettier

Semantically similar articles hand-picked by GPT-4

- Parsing JavaScript with JavaScript

- Livecoding #39: Towards an AI that writes JavaScript

- LOLCODE-to-JavaScript compiler babel macro

- How to debug unified, rehype, or remark and fix bugs in markdown processing

- How to debug unified, rehype, or remark and fix bugs in markdown processing

Learned something new?

Read more Software Engineering Lessons from Production

I write articles with real insight into the career and skills of a modern software engineer. "Raw and honest from the heart!" as one reader described them. Fueled by lessons learned over 20 years of building production code for side-projects, small businesses, and hyper growth startups. Both successful and not.

Subscribe below 👇

Software Engineering Lessons from Production

Join Swizec's Newsletter and get insightful emails 💌 on mindsets, tactics, and technical skills for your career. Real lessons from building production software. No bullshit.

"Man, love your simple writing! Yours is the only newsletter I open and only blog that I give a fuck to read & scroll till the end. And wow always take away lessons with me. Inspiring! And very relatable. 👌"

Have a burning question that you think I can answer? Hit me up on twitter and I'll do my best.

Who am I and who do I help? I'm Swizec Teller and I turn coders into engineers with "Raw and honest from the heart!" writing. No bullshit. Real insights into the career and skills of a modern software engineer.

Want to become a true senior engineer? Take ownership, have autonomy, and be a force multiplier on your team. The Senior Engineer Mindset ebook can help 👉 swizec.com/senior-mindset. These are the shifts in mindset that unlocked my career.

Curious about Serverless and the modern backend? Check out Serverless Handbook, for frontend engineers 👉 ServerlessHandbook.dev

Want to Stop copy pasting D3 examples and create data visualizations of your own? Learn how to build scalable dataviz React components your whole team can understand with React for Data Visualization

Want to get my best emails on JavaScript, React, Serverless, Fullstack Web, or Indie Hacking? Check out swizec.com/collections

Did someone amazing share this letter with you? Wonderful! You can sign up for my weekly letters for software engineers on their path to greatness, here: swizec.com/blog

Want to brush up on your modern JavaScript syntax? Check out my interactive cheatsheet: es6cheatsheet.com

By the way, just in case no one has told you it yet today: I love and appreciate you for who you are ❤️