This is a debate I keep getting into with all sorts of people. No matter how well I try explaining it people simply do not want to believe me they're thinking about distance all wrong.

After last weekend's trek around a very sunny city where I was forced to keep walking in the blistering noon sun, just because "It's closer!" and my sister is a naggy teenager and gets her way, I've decided to write this post wherein I explain once and for all the difference between intuitive distance and real-world distance.

Intuitive distance

First let's talk a little bit about how all of us think of optimizing our paths for distance.

You've probably noticed bits of grass so destroyed around the corners of walkways in parks that eventually the walkways are just expanded with rounded corners. Some architects are even so smart as to design them this way in the first place!

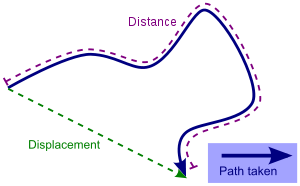

This is due to how right triangles work. The rule is basically that for any right triangle the length of the hypotenuse will necessarily be shorter than the sum of its catheti.

You can quickly check this is true with the first pythagorean triplet (3,4,5). Obviosly 5 is less than 3+4. Far from a rigorous proof, but the idea isn't stupid.

This is something that comes very intuitively to us. See a right triangle and choose to walk diagonally, it's simply shorter that way.

It's even more obvious when you think about it in terms of distance traveled versus displacement. The shortest path to take between two points will always be one that best fits displacement.

Taxicab Geometry

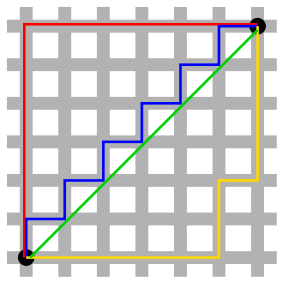

All of this comes crashing to a halt in large american cities. Those tend to be laid out in a grid, and prevent us from traveling over proper diagonals. Instead we follow diagonals to our best abilities alongside a grid.

Herman Minkowski stipulated in the 19th century that because of this constraint, the distance traveled diagonally is no different than the distance traveled on any other gridded path with the same displacement.

By looking at the sketch, I think we can all agree with Minkowski.

Distance as a parameter of cost

But taxicab geometry only works in the US and other cities laid out in a grid, I haven't really seen many of them. So maybe in Europe our intuition still works?

Everything becomes much more interesting once we start thinking of distance as a parameter of the function of cost.

Imagine you have to travel across a city. You can take a very short path through the streets. This path runs on smaller roads, which have a lot of crossroads, many red lights, people waiting to turn left and so on. Another path, a much longer one, runs mostly on larger roads where you have fewer stop lights and everyone waiting to turn left is ushered into their own lane.

Which path do you take?

It's probably obvious, but I've been in plenty of fights for taking the longer route.

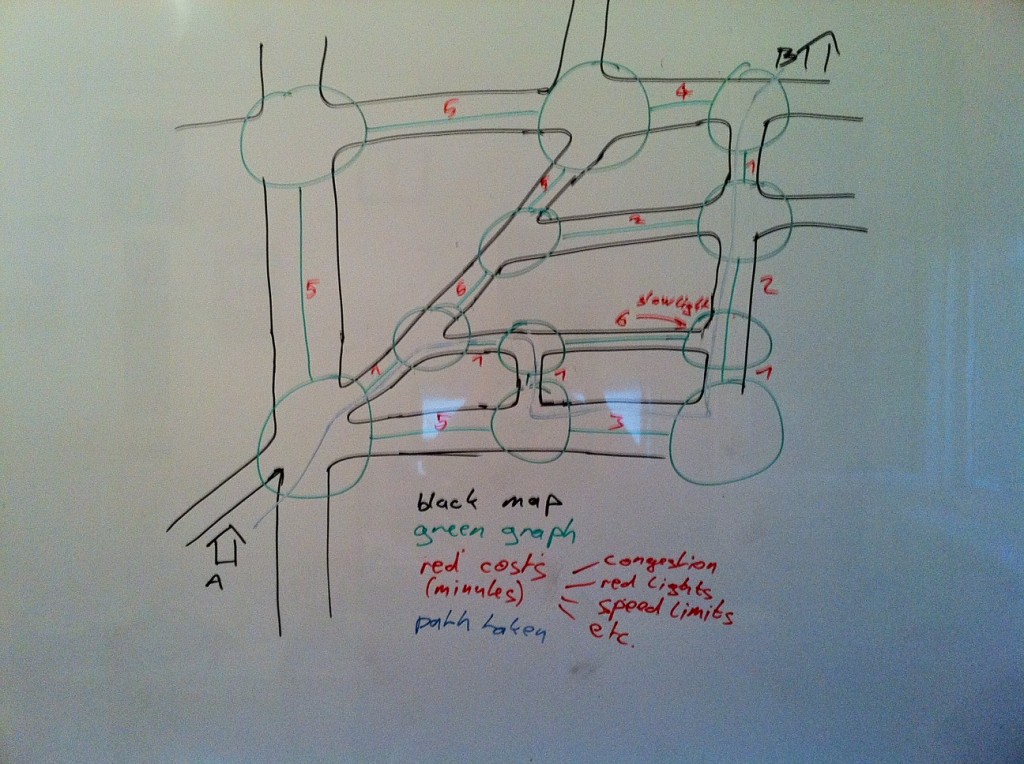

The whole problem boils down to something computer scientists and probably most mathematicians call graph traversal and finding the shortest path through a graph.

Basically it goes like this: You have a set of nodes connected with edges. Each edge has a number assigned to it. Find the path from node A to node B with the smallest total sum of traversed edges.

That number is completely abstract, it can mean distance or can be a function of many parameters telling you how costly it is to travel alongside that edge; it essentially doesn't matter, whatever you want to optimize for, that's how you define the function.

When walking I like to account for amount of sunlight ... especially in the summer.

There are many ways to approach solving this problem, but the algorithm Dijkstra came up with seems to work the best in most cases.

To illustrate my point, look at the pretty picture I've drawn on my whiteboard. Imagine this is a map of a few streets - geometric distance accounts for our intuitive understanding of distance. The cost I've chosen to optimize for is time.

Point proven? Or at least shown? Can I just send this link every time I get into this discussion?

But the most interesting bit, I think, is how a lot of people think like this in a car. Why not on foot? Or on a bike? What makes those ways of traveling so much different that suddenly physical distance traveled is the only factor we think about? No matter how many things I have to climb over, I will fucking walk the shortest path!

Really?

PS: another interesting example is the Mythbusters Waterslide Wipeout episode, where they show a mail truck doing only right turns (in the US) saves fuel despite traveling a much greater physical distance.

Continue reading about Our intuitive understanding of distance fails us

Semantically similar articles hand-picked by GPT-4

- A month on the road

- Architecture is like a path in the woods

- I learned two things today 5.8.

- The bliss and curse of mindsets

- Science Wednesday: Self-driving cars

Learned something new?

Read more Software Engineering Lessons from Production

I write articles with real insight into the career and skills of a modern software engineer. "Raw and honest from the heart!" as one reader described them. Fueled by lessons learned over 20 years of building production code for side-projects, small businesses, and hyper growth startups. Both successful and not.

Subscribe below 👇

Software Engineering Lessons from Production

Join Swizec's Newsletter and get insightful emails 💌 on mindsets, tactics, and technical skills for your career. Real lessons from building production software. No bullshit.

"Man, love your simple writing! Yours is the only newsletter I open and only blog that I give a fuck to read & scroll till the end. And wow always take away lessons with me. Inspiring! And very relatable. 👌"

Have a burning question that you think I can answer? Hit me up on twitter and I'll do my best.

Who am I and who do I help? I'm Swizec Teller and I turn coders into engineers with "Raw and honest from the heart!" writing. No bullshit. Real insights into the career and skills of a modern software engineer.

Want to become a true senior engineer? Take ownership, have autonomy, and be a force multiplier on your team. The Senior Engineer Mindset ebook can help 👉 swizec.com/senior-mindset. These are the shifts in mindset that unlocked my career.

Curious about Serverless and the modern backend? Check out Serverless Handbook, for frontend engineers 👉 ServerlessHandbook.dev

Want to Stop copy pasting D3 examples and create data visualizations of your own? Learn how to build scalable dataviz React components your whole team can understand with React for Data Visualization

Want to get my best emails on JavaScript, React, Serverless, Fullstack Web, or Indie Hacking? Check out swizec.com/collections

Did someone amazing share this letter with you? Wonderful! You can sign up for my weekly letters for software engineers on their path to greatness, here: swizec.com/blog

Want to brush up on your modern JavaScript syntax? Check out my interactive cheatsheet: es6cheatsheet.com

By the way, just in case no one has told you it yet today: I love and appreciate you for who you are ❤️